Performance Tips

Tips for fixing common problems you might encounter in your application.

Ship First, Optimize Later

Like many in the Ruby community, we value developer productivity and writing beautiful, maintainable code. Of course it’s important to be mindful of performance when writing framework code. That said, when it comes to working on our apps, we’d rather spend our precious time (and brain cycles!) shipping new features. Hoisting variables and tearing apart nested loops is fun and all, but not the best use of time if we can help you avoid it.

With Skylight, you can rest easy knowing that we’ll give you a heads up on any potential performance problems. That way, you can focus your limited time in the places where it matters to you the most.

Here are some performance concepts that are useful to know about. Don’t worry though! Skylight will help you find these issues in your app, and you can always revisit these tips when you come across an issue.

Hot Paths

What do we mean by hot paths? In short, loops. A piece of code that takes 50ms or produces 200 objects might be completely fine if called occasionally; but if you call that code thousands of times in a loop, it can really add up. This is even worse if you nest loops inside of other loops, where a small piece of code can inadvertently be run hundreds of thousands of times.

Hidden Loops

All of this might seem obvious, but in a high-level programming language like Ruby, it’s very easy for loops (or even nested loops) to be hidden in plain sight.

Some clues that you have a hidden loop:

- Methods on

Enumerableor other collections, likeeachandmap(especially when using&:, also known as the pretzel operator). - Active Record associations and other relations (like

user.appsor callingdestroy_allon a relation). - APIs that work with files and other IO streams.

- APIs in other libraries, especially APIs that take collections and/or blocks.

Keep in mind that the problem is not the loop itself, but rather that the loop amplifies the effect of any repeated work. Therefore, there are two basic strategies to fixing the problem: loop less, or do less work in each iteration of the loop

Iterate Less

One of the most common ways to reduce the number of iterations you do in Ruby is to use Active Record methods to combine work and take advantage of your database for the heavy-lifting.

For example, if you’re trying to get a list of unique countries across all your users, you might be tempted to write something like this:

User.all.map(&:country).uniq

This code fetches all the user records from your database, looping through them to create an Active Record object for each row. Next, it loops over all of them again to create a new array containing each country. Finally, it loops over this array to de-dupe the countries in Ruby.

As you can see, this approach ended up doing a lot of wasteful work, allocating many unnecessary intermediate objects along the way. Instead, you could make the database do the work for you:

User.distinct.pluck(:country)

This generates a SQL query that looks like:

SELECT DISTINCT "country" FROM "users";

Instead of making intermediate Ruby objects for every user and looping over those objects multiple times, this directly produces the array of countries in the database itself. This not only does less work in your application, but it also significantly reduces the work that your database has to do.

Another benefit of pluck is that once the raw data is transmitted back to the database adapter, it is transformed into Ruby primitives, which are much lighter-weight than Active Record objects.

This technique works for updating and deleting too. Instead of iterating over the objects you want to change in Ruby:

User.where("last_seen_at < ?", 1.year.ago).each(&:destroy)

You can do the same thing in the database directly:

User.where("last_seen_at < ?", 1.year.ago).delete_all

This generates a SQL query that looks like:

DELETE FROM "users" WHERE last_seen_at < ...;

IMPORTANT:

When you use delete_all, the database is in charge of deleting the records. Your Active Record validations and callbacks will not run, so you might not always be able to use this technique. This is also true about update_all.

If you find yourself looping over Active Record objects in Ruby, there is likely a way to shift some of the work to the database. The Active Record Query Interface guide is a good place to start.

Along the same lines, when looping through a large number of Active Record objects, consider using batching APIs such as find_each. While they don’t ultimately reduce the total number of allocations, they ensure that you are holding on to fewer objects at the same time, allowing the garbage collector to work more effectively.

Do Less Work Per Iteration

If you have a loop in a hot path that absolutely must exist, you should try to find ways to improve performance inside each iteration of the loop.

The quickest wins here involve:

- moving shared work outside of the loop (for example, into a background job),

- doing less work in Ruby and more in the database (as shown here),

- and looking for seemingly benign constructs do more work that you’d expect (as shown here).

Repeated Queries

Skylight highlights endpoints that repeatedly make similar SQL queries with the database “heads up” icon:

When you click on an endpoint with the database “heads up”, Skylight calls out repeated queries with a loop icon:

In general, you will get better performance out of your database if you group together similar queries. For example, let’s say your application is making these queries:

SELECT * FROM "monsters" WHERE "id" = 12; SELECT * FROM "monsters" WHERE "id" = 15; SELECT * FROM "monsters" WHERE "id" = 27;

It would be more efficient to make a single SQL query:

SELECT * FROM "monsters" WHERE "id" IN (12, 15, 27);

Possible Cause: Queries in Loops

N+1 Queries

“N+1 Queries” are a very common cause of repeated queries in Rails applications. This happens when you make a request for a single row in one table, and then make an additional request per element in a has_many relationship, usually in a loop.

Here’s an example offender (inspired by the the Rails guides):

monsters = Monster.limit(10) monsters.each do |monster| puts monster.favorite_food.name end

The mistake here is that you’re making a single query for ten Monsters, but then one query for each Favorite Food to get its name, something like this:

SELECT * from "monsters" LIMIT 10; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 7; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 8; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 10; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 12; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 13; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 15; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 16; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 17; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "id" = 21;

Sometimes, these loops are less obvious. For example, map uses a loop under the hood. The following code would generate the same set of queries as above:

monsters = Monster.limit(10) favorite_foods = monsters.map { |m| m.favorite_food.name }

And sometimes the initial query and the loop are in completely separate files. Again, the following code would generate the same set of queries:

# app/controllers/monsters_controller.rb def index @monsters = Monster.limit(10) end

<%# app/views/monsters/index.html.erb %> <% @monsters.each do |monster| %> <p><%= monster.favorite_food.name %></p> <% end %>

These hidden N+1 queries can be difficult to identify. Fortunately, Skylight has your back.

Skylight automatically normalizes the above repeated queries into the following “description,” allowing us to detect the repetition and show you “heads ups” in the UI. This description is what you will see in the Skylight.

SELECT * FROM "monsters" WHERE "id" = ?;

Solving the N+1 Query Problem

The solution to this problem is “eager loading”, which means specifying ahead of time which associations you will need. For the example above, we can specify that we want to load the Favorite Food association when for each Monster when we load the Monster:

monsters = Monster.includes(:favorite_food).limit(10) favorite_foods = monsters.map { |m| m.favorite_food.name }

Now, Rails will generate the following SQL for you ahead of time, before you get to the map:

SELECT * from "monsters" LIMIT 10; SELECT * from "favorite_foods" WHERE "monster_id" IN (7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 21);

When we tell Active Record to include the Favorite Foods when it loads the Monsters, Active Record will inspect the results for the required monster_ids and make an additional query to the Favorite Foods table, quietly inserting records into the appropriate association caches in the background. Then when a future loop (even one in the template!) needs to find a Monster’s Favorite Food, it will find the data has already been loaded and use that data instead.

Other Possibilities

Skylight will report any kind of repeated database query that includes more than four repetitions and consumes more than 50ms on a regular basis.

Not all repeated queries can be resolved using the “eager loading” technique described above (for example, INSERT statements). In these cases, there are some other strategies you can try.

Look for any hot paths that affect your endpoint, then loop less or do less work in each iteration of the loop within these hot paths. Consider moving repeated, slow queries into background jobs if possible.

Allocation Hogs

Your Rails app is probably humming along just fine most of the time. Still, your users probably have the occasionally painfully slow request seemingly at random. While unexplained slowdowns can happen for many reasons, the most common root cause is excessive object allocations.

Garbage Collection Pauses

When you create objects in Ruby, they eventually need to be cleaned up. That cleanup (garbage collection, or GC) usually happens far away from the code that created the objects in the first place.

Even worse, it’s not uncommon for the garbage collection to happen in a completely different request. Each request has a small chance of tipping the scales and triggering a GC run, resulting in seemingly random slowdowns for your users.

While this explains the mystery, it doesn’t help resolve the problem. Fortunately, Skylight tracks object allocations throughout your requests, helping you zero in on parts of your app that are doing the most damage.

Identifying Allocation Hogs

Endpoints with allocation hogs are identified in Skylight with the pie-chart “heads up”:

By default, Skylight focuses on how much time your endpoints and events are taking. When you drill down into an endpoint, you will see a representative trace for that endpoint where the larger bars represent events that took a long time to complete. When you switch to allocations mode, the same trace will be re-scaled based on the number of allocations during each event, allowing you to quickly identify potentially problematic events (i.e. the largest bars in your traces).

Fixing the Problem

Now that you’ve zeroed in on exactly which part of your app to work on, let’s talk about the most effective ways to reduce allocations.

Pro Tip:

Before you spend weeks applying the tips in this section to every line of code, here’s a disclaimer: reducing allocations is a micro-optimization. This means that they produce very little benefit outside of hot paths and that they may reduce your future productivity (which may reduce your ability to do important macro-optimizations like caching). Be sure to use Skylight to identify allocation hot spots and focus your energy in those areas.

First, identify the hot paths for your endpoint.

Here’s a simplified example we saw recently when using Skylight to identify memory hotspots in our own app:

def sync_organization(organization) Mixpanel.sync_organization(organization) organization.users.each do |user| Mixpanel.sync_user(user) end end

At first glance, you can see that this code has a loop, but it looks pretty innocuous. However, the sync_user method calls into a 30-line method that contains many lines that look like this:

user.apps.includes(:organization).map(&:organization)

Here, we are looping through each user in an organization, then looping through all the apps for each user. Now imagine that sync_organization itself is called multiple times in a single request. You can see how this can quickly add up.

This short line of code involves multiple hidden loops, allocating a large number of intermediate objects. When digging in to an allocation hot spot, the first step is to identify loops, and you should especially be on the lookout for these hidden loops, because they are very easy to miss.

Allocate Fewer Objects Per Iteration

If you have a loop in a hot path that absolutely must exist, you should try to find ways to allocate fewer objects inside each iteration of the loop.

The quickest wins here involve moving shared work outside of the loop and looking for seemingly benign constructs that need to allocate objects. Let’s look at this hypothetical example:

module Intercom def self.sync_customers Intercom.customers.each do |customer| if customer.last_seen < 1.year.ago customer.deactivate! end if blacklisted?(domain: customer.email.domain) customer.blacklist! end log "Processed customer" end end def self.blacklisted?(options) ["hacked.com", "l33t.com"].include?(options[:domain]) end end

In this seemingly simple example, there are multiple places where we are allocating unnecessary objects in each iteration:

- The call to

1.year.agocreates multiple new objects in every iteration. - The call to

blacklisted?function allocates a hash ({ domain: customer.email.domain }). - The call to

logallocates a new copy of the string"Processed customer". - The method

blacklisted?allocates an array (along with the strings inside it) every time it is called.

A slightly different version of this loop has many fewer allocations:

# frozen_string_literal: true module Intercom def self.sync_customers inactivity_threshold = 1.year.ago Intercom.customers.each do |customer| if customer.last_seen < inactivity_threshold customer.deactivate! end if blacklisted?(domain: customer.email.domain) customer.blacklist! end log "Processed customer" end end BLACKLIST = ["hacked.com", "l33t.com"] def self.blacklisted?(domain:) BLACKLIST.include?(domain) end end

Depending on how many customers this code is looping over, we might have saved a large number of allocations here:

- We hoisted

1.year.agooutside the loop, so we allocate only one shared copy for the entire loop. - We changed

blacklisted?to take keyword arguments, which eliminates the need for the hash since Ruby 2.2. - We moved the blacklist array to a constant, so it is shared across calls.

- We used

# frozen_string_literal: true, which guarantees that a single string will be created and reused since Ruby 2.3.

The last point deserves a special mention: by guaranteeing the immutability of your string literals, Ruby can reuse the same instance of the string object across multiple calls. This essentially allows Ruby to hoist the string for you (similar to how we moved the blacklist into a constant) while keeping the string inline for readability.

The # frozen_string_literal: true magic comment freezes all of the strings in the file. If you don’t want this behavior, you can use the “unary minus” operator instead: -"Processed customer". Regular expressions, integers (Fixnums), and most floating point values already receive similar optimizations in modern Rubies, so you normally wouldn’t have to worry about hoisting them manually.

Expensive Views

One of the easiest ways to get a decent performance boost out of a Rails app is to find ways to cache expensive HTML or JSON fragments.

Identifying Expensive Views

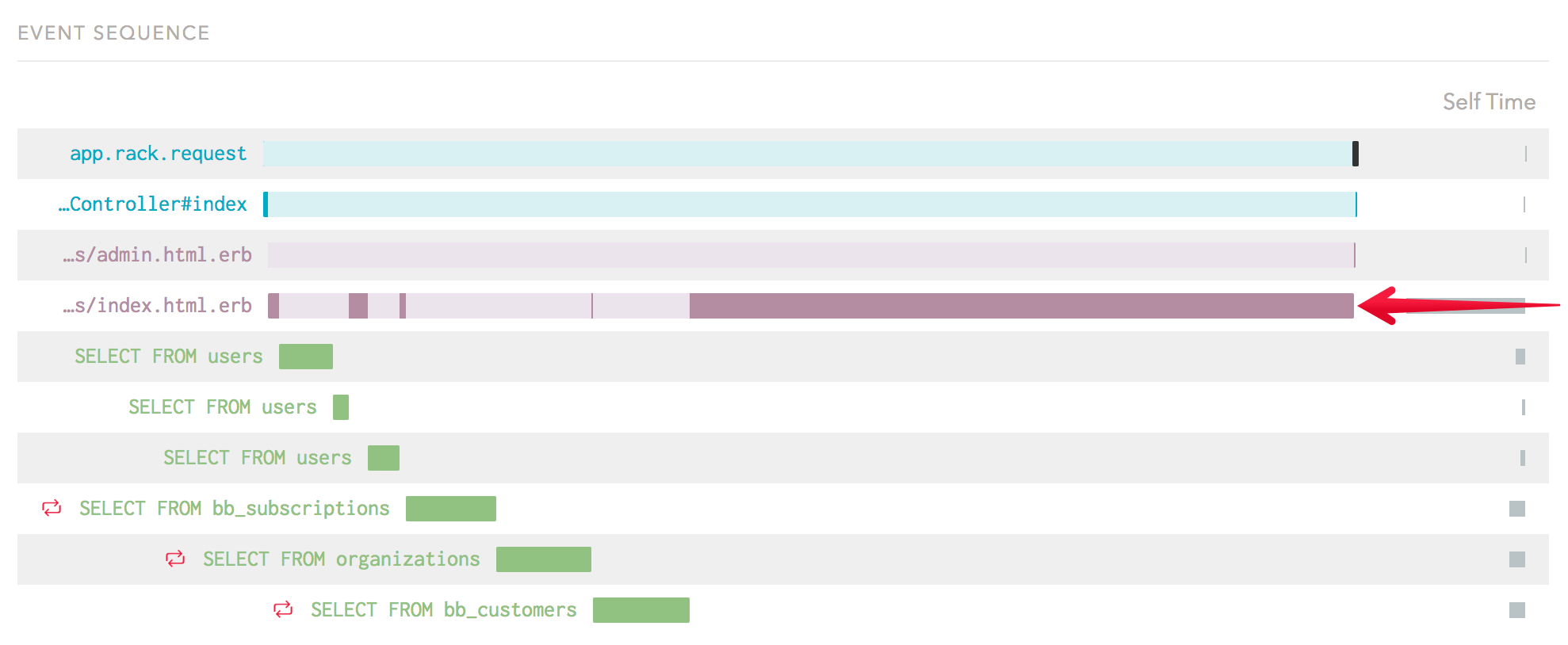

To get the best bang for your buck, you should focus your energy on areas of your templates that are doing the most work. Using Skylight, you can look at your endpoint’s Event Sequence to get a sense of which templates to focus on. In this example, the bulk of the time is actually spent in just one HTML fragment:

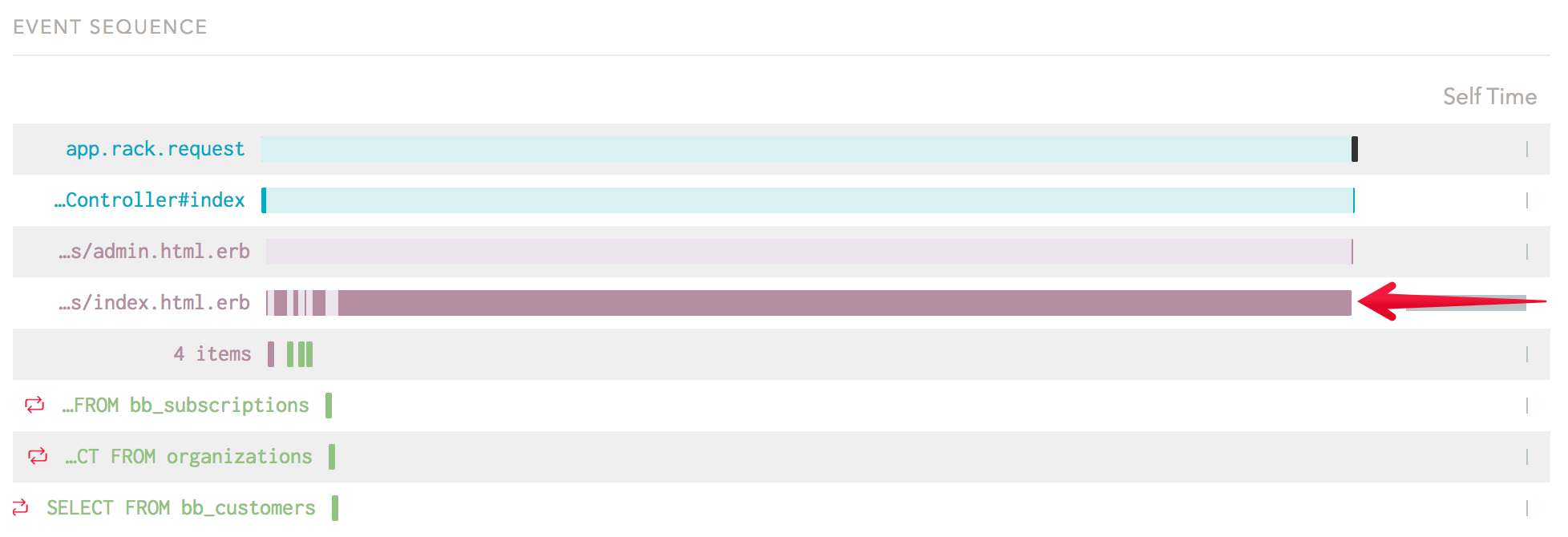

Additionally, the bulk of the allocations for this endpoint occur within the same HTML fragment:

Adding caching to this template will improve time spent for this endpoint and reduce garbage collection pauses across the application.

Use Basic Fragment Caching

Looking into index.html.erb, we find a few truly dynamic bits, like this:

<%= render partial: 'shared/flash',

locals: { flash: flash, class_name: "banner" } %>

But for the most part, it’s a large template whose dynamic bits look like this:

<%= link_to "Sign Up For Free", signup_path, class: 'signup' %>

Fortunately, Rails makes caching really easy! Just wrap the area of the template that you want to cache with a cache block:

<% cache(action_suffix: "primary") do %> <section class="hero"> <div class="container"> ... </div> </section> <section class="data"> <div class="container"> ... </div> </section> <% end %>

When using fragment caching, remember three things:

- Pick a key that describes the fragment you are caching. You can use

action_suffix, as in this example, if the key is unique only inside of this action. (You can also use an Active Record object as your cache key, which is quite convenient and simple in the right situations.) - The easiest caching backend is memcached. This is because memcached automatically expires keys that haven’t been used in a while (an “LRU” or “least recently used” expiration strategy), and cache expiration is the hardest part of a good caching strategy.

- Focus on the big spenders. It’s tempting to spend a lot of time caching all of your HTML and trying to identify good cache keys for everything. In practice, you can get big wins by just caching expensive fragments that have easy cache keys (either because the template is relatively static, or because they’re derived from an Active Record object, which has built-in caching support).

Synchronous HTTP Requests

When you’re just starting out, it’s too easy to make synchronous HTTP requests inside your requests, because why not? Getting a worker setup up and running takes time and it adds operational cost to your app while you’re still trying to get it off the ground (usually with a tiny team).

Once you get going though, synchronous HTTP requests are one of the biggest culprits when it comes to slow requests. It’s also easy to lose track of them because you’re likely synchronizing with third party services in before_filters or middlewares, two areas of code you don’t look at very often.

Identifying Slow Synchronous HTTP Requests

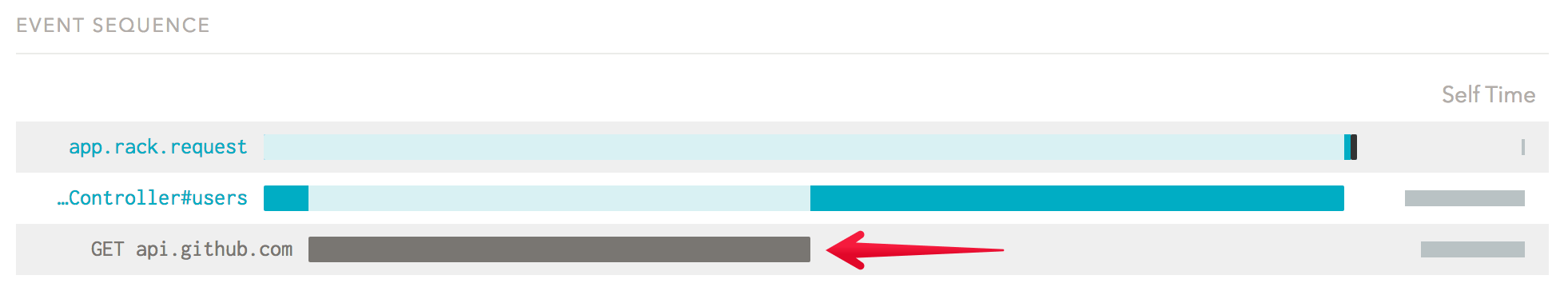

When using Skylight, be on the lookout for grey boxes indicating synchronous HTTP requests:

In most cases, you can collect quick wins by moving this work from your request/response cycle into a background worker.

Move Third-Party Integration to Workers

Or, put another way: do as little as possible in your request.

One of the biggest things we did to improve the Skylight Rails app over time was to move third-party integrations (like updating Intercom or notifying Slack) from the request itself into a worker.

If you feel daunted by the process of getting background jobs up and running, don’t! It’s one of the highest leverage improvements you can make to a Rails app. Once you have the ability to send work to background jobs, you’ll be surprised how often you use it.

If you’re using Rails 4.2 or newer, ActiveJob makes the process even simpler. Rails now seamlessly bakes the notion of background jobs into the framework, complete with generators to get you started. We strongly recommend it.